WHAT DO THE MAIN ECONOMIC PARADOXES TELL US?

Let’s take a journey through some of the strangest — but very real — exceptions to the rules of supply and demand.

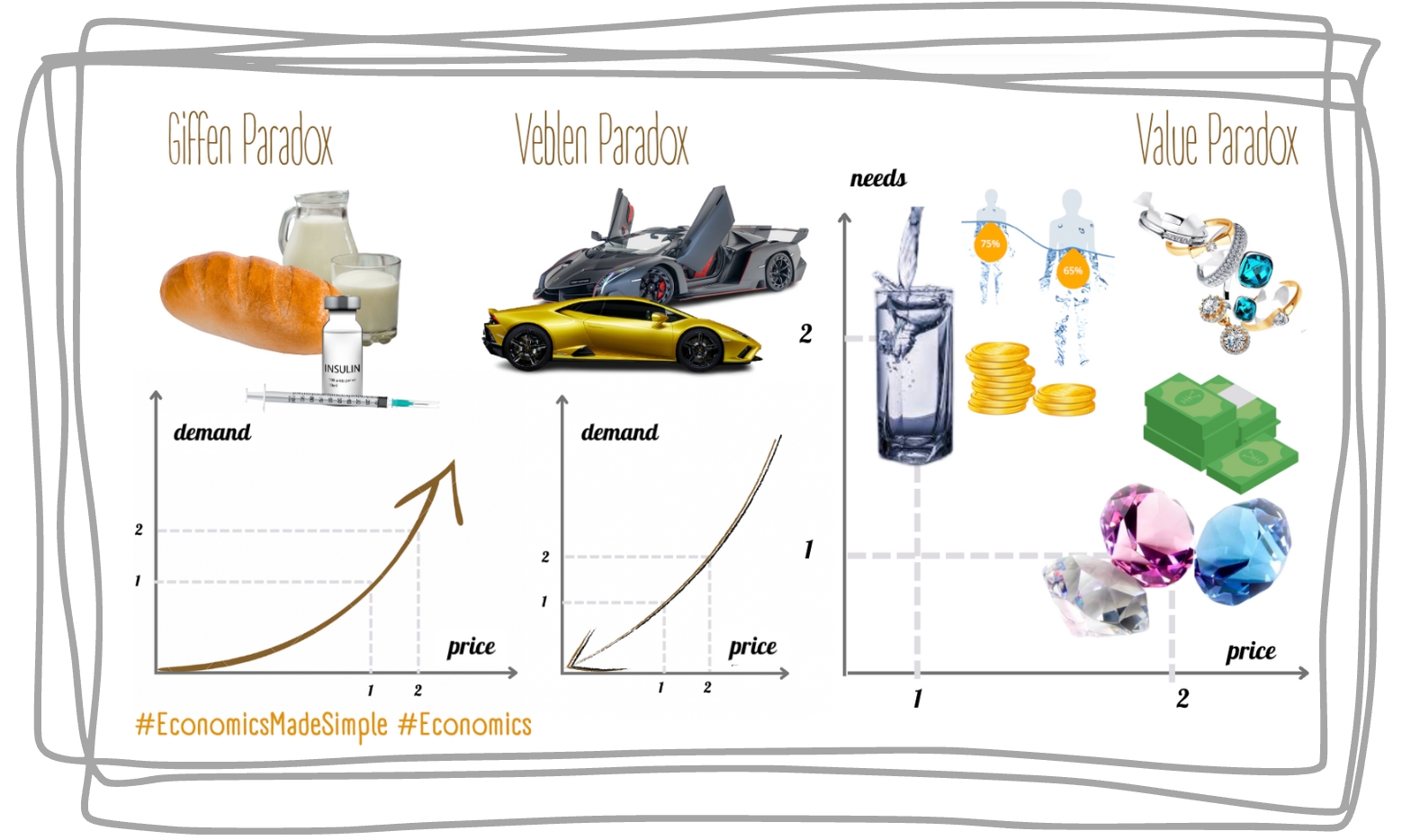

First, the Giffen Paradox, which in some ways contradicts the Law of Demand, was discovered during the Great Famine of 1845–1849 in Ireland. At that time, potatoes were the main staple food in the country, and although their prices quietly increased due to poor harvests, their consumption actually went up. In other words, there are goods for which a price increase leads to higher demand. Since then, so-called Giffen goods have included low-quality, inferior goods that make up a significant share of a consumer's budget. In this context, bread is a typical example of such a good.

Next is the Veblen Paradox, which also breaks the Law of Demand. For certain goods, a price drop is not followed by an increase in demand, but rather a decrease. Imagine owning a limited-edition Lamborghini. It’s not practical, clearly not meant for grocery runs, but it perfectly reflects your status as someone who can afford one of the rarest cars in the world. This is known as conspicuous consumption, where the motivation for buying a good or service is not the objective need but the subjective desire to demonstrate one's financial capability. The higher the price, the higher the demand for such a product.

Have you ever wondered why something as essential as water costs far less than diamonds, which are hardly useful in everyday life? This is known as the Value Paradox, formulated by Adam Smith. It highlights that goods satisfying secondary needs (gold, platinum, diamonds) are often more expensive than those meeting primary needs (water, bread, clothing). Economic theory later explained this through the rarity of goods and the principle of diminishing marginal utility. Price (and demand) is influenced by marginal utility: when water is abundant, its price is low; when diamonds are rare, their price skyrockets.

WHAT IS A "WHITE ELEPHANT" AND WHY DO WE NEED A MARKET?

A "white elephant" is an English idiom describing something costly but impractical and useless. It refers to an object whose maintenance costs exceed its actual value.

The expression originates from Siam (modern-day Thailand), where, according to legend, the king would gift white elephants to courtiers he disliked. This "royal favor" would ruin them, as they couldn’t refuse the gift, yet its upkeep was unbearably costly.

Examples of "white elephants" include airports, stadiums, iconic buildings, and oversized transport systems. One such case was the Montreal–Mirabel International Airport in North America, once planned to handle 50 million passengers annually. Over 40,000 hectares of productive farmland and forest were expropriated for its construction. The airport opened on October 4, 1975, but with only one terminal. By 1985, Canadian Prime Minister René Lévesque called it a "historic mistake" and "a national embarrassment." Mirabel operated for passenger flights until October 31, 2004. A decade later, maintaining the facility had cost around $30 million, and in 2014, it was decided the terminal would be demolished.

Another example is linked to eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes, who during World War II developed a massive wooden flying boat weighing 136 tons, designed to transport 750 soldiers. The plane completed just one flight, lifting off to 21 meters before landing. Despite his mental health issues, Hughes spent $1 million annually until his death to keep the aircraft operational.

So, what does this have to do with the market economy? The point is, the market would never pay for such things. These "white elephants" are more likely to be built either by millionaires — as personal whims — or by government bodies — as populist monuments of fake grandeur (Maxym Obyzan).

Millions of people possess far more information than any single state official. That’s why the market gathers and processes information better than individual planners. It also operates far more efficiently than the state or monopolies. Ideally, markets must be competitive because consumers "vote" with their money, and producers through their profits.

COMPETITION is the greatest good: when producers lower prices in a struggle for consumers, it is the consumer who wins.

#SimplyAboutEconomics #Economics #EconomicParadoxes #MarketLogic #Competition #WhiteElephant #GiffenParadox #VeblenEffect #EconomicsExplained